.

The coronavirus crisis occurred during my final year in seminary, after my classmates and I had just completed a rigorous series of final activities and exercises required for ordination to the priesthood. In late January, we underwent 72 hours of written and oral comprehensive exams, testing everything we had studied over the past five years about theology, liturgy, the sacraments, spirituality, ecclesiology, the history of the church, and pastoral care.

.

Things happened in rapid succession after that. We wrote letters to our bishops, petitioning for ordination and we underwent our final “scrutinies,” in individual sessions with the rector. The purpose of these scrutinies was to affirm that we knew what would be required of us as priests and that we were entering this new stage of our lives voluntarily.

.

In the midst of all of this, we continued our ongoing responsibilities and relationships with members of the parishes we had been assigned to in Baltimore. We baptized babies, led novenas, delivered homilies, served during mass, interviewed candidates for confirmation, and comforted and counseled parishioners who were experiencing significant transitions in their own lives.

.

Reports of the spreading coronavirus hovered in the background of all this. First, there were newspaper reports about how the virus was spreading in China. These reports began last December. We read about how the virus had spread to Iran and Italy, and about the precautionary measures that governments had taken in South Korea and Japan. There were ominous warnings that it would only be a matter of time before the virus spread to the U.S.

.

Still, our lives and our relationships continued and grew even deeper. I spent time with friends, both seminarians and people I met in Baltimore. We went to restaurants and movies and visited different parishes on Sundays when we were not required to serve in our assigned parishes. We hung out in coffee shops, shared memories and shared our hopes for the future. There were hugs, handshakes, and pats on the back, the kind of physical contact that everyone needs, the contact that makes us human and connects us to one another.

.

A conversation that I had about philosophy with a seminarian from Columbia reminded me of how much I used to enjoy reading the works of Albert Camus, many years ago. As a result, I bought a copy of Camus’ “The Plague,” and began to re-read it for the second time in about forty years.

.

I went for long walks, sometimes alone, sometimes with other seminarians, through the woods and the green fields on the campus. A seminarian from Vietnam and I talked about English idioms that make the English language difficult to learn. We talked about what it was like to grow up in the United States and in Vietnam. We cooked meals, shared jokes, laughed and sang together. We also watched movies and accompanied each other in prayer.

.

Among the movies we watched were “Les Miserables,” Charlie Chaplin’s “City Lights,” and “The Kid,” and “Tsotsi,” a film from South Africa that was shot in a shantytown in Johannesburg. Disturbingly, however, when we went to the supermarkets to shop for food many of the shelves were bare. As we walked through the aisles of several pharmacies, there were no longer any cleaning supplies, antiseptic alcohol, or thermometers. The empty shelves starkly mirrored the efforts of customers to keep a distance from one another. Suddenly touch, any form of physical contact was forbidden.

.

The warnings about the spread of the coronavirus continued. By now, the rector at St. Mary’s began giving almost hourly updates on the progression of the virus in the United States and the precautions that the Center for Disease Control, (CDC) was recommending. He explained that although it was his desire to keep the seminary open for as long as he could while protecting our safety, all options were now on the table, including the possibility of closing the seminary itself and sending us home. He instructed us to have minimal contact with the outside world beyond the walls of the seminary.

.

I had gotten to know the employees and some of the customers at several of the coffee shops in the area. In many ways, each coffee shop is a community in itself. I decided to make final visits to the shops, both to stock up on whole beans so that I could brew fresh coffee in my room, and to say good-bye to people I began to suspect I would not see again for a long time.

.

One of the baristas, who was in her senior year in high school, confided during her break that she was upset that she would not be able to celebrate her graduation as she had dreamt of doing for many years. She said that it bothered her that she would lose the 400 dollars she paid toward several graduation events that had now been canceled. Her school told her that the money that she paid through her savings while working at the coffee shop over the past year, was non-refundable. Above all, she said she would miss not having the opportunity to bring together her family and her friends for this important milestone in her life. I commiserated with her in her disappointment, but as I left the coffee shop it crossed my mind that this might affect the graduation events at St. Mary’s, and perhaps the celebrations I was planning for my ordination.

.

As the virus continued to spread, precautions increased and institutions all around us began to shutter their doors. Public amenities, such as a portable coffee cart in the Seminary’s hallway, suddenly disappeared. The theological library was now closed to the general public. The Ecumenical students, who normally take classes at the seminary in the evening, started to dwindle. Eventually, the Ecumenical Institute switched to on-line courses. The CDC was now issuing warnings that gatherings should be no larger than 50 people. Many seminarians had resolved to tough it out until Palm Sunday, when we would have to return to our home dioceses anyway, for two weeks, before returning to St. Mary’s to finish the semester. These hopes were soon dashed when the CDC issued projections for the virus to reach its peak in early May. Despite our voluntary semi-quarantine within the seminary, there seemed to be little hope that we would return after Easter break. The Archbishop of the Archdiocese of Baltimore instructed parishes to discontinue all public Masses because the crisis was worsening.

.

Still, for us, there was work to be done. There were obligations to fulfill, and relationships to maintain. It was the midterm season and we were now immersed in preparation for yet another round of exams. We faced long periods of intensive study. We also had to deliver class presentations. No one wanted to be seen as being unprepared for whatever questions they might get during these presentations. My tutoring shifts at the Writing Center in the library, where I helped other students revise their papers, had a steady stream of visitors to the point where my eyes became red and my vision was blurred by the end of the night. Nonetheless, there was comfort in community-living and there was the fullness of life in our activities. In my exhaustion, I paused each night as I passed the chapel and offered a brief prayer in silence before going to bed.

.

On Monday, after a vigorous class discussion, I headed to my room to get the latest updates on the coronavirus before going to Mass when one of the seminarians stopped me in the hallway and said, “You know you’re the deacon for Mass today, right?” In my scramble to complete the work on my midterms and to prepare for class presentations, I had forgotten to check the schedule for my clerical assignments for the week. I rushed into the sacristy and vested for Mass. The priest who was the celebrant of the Mass and I lined up with the servers to begin the procession into the chapel but the rector, who had been giving regular updates on precautions our community should be taking to prevent the spread of the coronavirus signaled for us to stop because he had yet another update to deliver.

.

The CDC was now advising to avoid public gatherings of more than 10 people. The celebrant and I couldn’t hear the rector very well because the acoustics were poor where we were standing, so we inched onto the sanctuary itself and stood close to the wall. The rector continued, “After meeting with the faculty and student advisory committees on the coronavirus, and after talking with Archbishop Lori, I am announcing that all classes will be suspended immediately after Mass and that the semester will be over and should return home.”

.

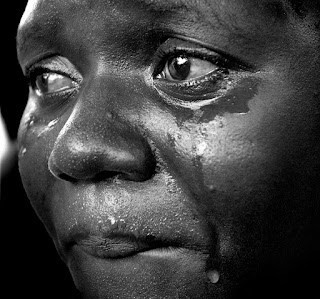

There was an audible gasp in the chapel as students and faculty realized that this would be our final Mass together as a community. The tone of the Mass was somber. Students who were in their final year in the seminary, and who had been ordained as deacons during the previous summer were stunned. It was suddenly over, but there would be no ritual or ceremony to mark the occasion. There would be no time for closure at the end of a long journey. Some of the deacons had spent seven years in the seminary; they openly wept when they realized they were receiving communion in the chapel as a seminarian for the final time.

.

As the liturgy drew to a close I gave the dismissal at the end of Mass, “Go forth, the Mass is ended,” to which the community somberly replied, “Thanks be to God.” The Mass had indeed ended and with it the semester, and, for the deacons, with the semester, the many years they had spent as seminarians.

.

I processed from the chapel with the priests singing a full-throated rendition of “Salve Regina” (Hail Holy Queen), a Marian hymn which is sung at the conclusion of most gatherings of priests or seminarians. The voices of the seminarians filled the chapel with the hymn. The priests continued to sing the hymn as they processed into the sacristy. The seminarians continued singing in the chapel.

.

At some point, on the way to the sacristy, the priests managed to get several lines ahead of the seminarians so that the echoing back and forth between the two groups of voices had a “call-and-response” effect. By the time the priests had reached the sacristy and stood in a semi-circle around a wooden crucifix above a cabinet inscribed with the words, “Sancta Sancte” (Holy, Holy), we heard the voices of the seminarians thundering through the stone walls of the chapel, singing the final lines of the Salve Regina.

.

I stared at the words, “Sancta Sancte,” inscribed with gold letters. The seminarians’ voices, as they concluded the hymn, several lines later than the priests, seemed forceful, almost to the point of being defiant. It seemed as though, at that moment, in spite of everything, the spirit of St. Mary’s was unbroken.

.

As the celebrant of the Mass bowed before the crucifix, we all bowed with him and he gently said, “Prosit,” (may it be for your benefit). We replied, “Pro omnibus et singulis,” (for all and for each).

.

The voices of the singing seminarians were breaking through the walls from the chapel. They echoed through the sacristy. The words “Sancta Sancte” blazed beneath the crucifix. I could not help but to think about what was going on in the world beyond the stone walls of the seminary. It was a world of scarcity, fear, and uncertainty. It was a world in which we were being called to minister. It would not be a neat world of comfortable predictability. We would have to adapt and adjust.

.

Our semester, and for many of us, years of formation had abruptly come to an end. It all felt incomplete. Yet, in this world of abrupt endings and uncertainty we would have to reach out, often putting ourselves at risk, and minister to a suffering world.

.

I often think of myself as being an introvert, but in the following 48 hours I began to realize how much I thrive within multiple communities. This was true, whether those communities were within the walls of the seminary or they were in the larger social and cultural environment that had become a part of my life in Baltimore.

.

People, relationships, I discovered, were important to me, yet under the present circumstances of the coronavirus I would suddenly have to practice “social distancing.” It all seemed unnatural. Like the virus itself, the situation ruthlessly tore apart relationships, contact, touch, and everything that makes a person human.

.

As Monday wore on the staff and lay faculty rushed around the building, collecting books and papers in boxes and sought last-minute assistance to help them set up their computers so that they could do their work from their homes. I helped some of the seminarians and staff members hastily gather their things for their departure and I was reminded, at that moment, of the scenes of “the fall of Saigon” from old news footage.

.

The next day, the faculty and staff from Ecumenical Institute were gone, as were most of the School of Theology staff for the seminary. All that remained was a dwindling population of seminarians, and they were loading up their cars so that they could leave as soon as possible, but many lingered. I helped a seminary brother from Vietnam move into his new location in a nearby rectory. We had been close friends ever since he arrived in August of last year, and we had grown even closer over the past three months. We had a final meal together before saying good-bye.

.

I spent the afternoon in the library of the seminary, forcing myself to push through a wall of emotional pain that threatened to immobilize me. I was beginning to feel the full brunt of the loss of so many members of my community. I hunched over a bookcase to organize my notes from the past seven months, preparing to scan them into digital files for my computer. I planned to transcribe them once I got back to my home diocese in Pittsburgh. It took over six hours to finish the project; the result was 65 digital documents averaging 15 pages each (approximately 975 pages of notes). My emotional pain was now coupled with physical exhaustion.

.

While I was in the middle of this photocopying binge, one of the students from the Ecumenical Institute, who had been auditing a class on literature that I was taking, came up to me with a bewildered expression, “Aren’t we having class today? I heard they are sending you all home.”

.

I nodded “yes,” they were sending us home and felt as though I had been gutted by a hunter’s knife. He said, “How do you feel about that?” I leaned on the top of the bookcase, searching for a way to describe what all of this was like. I told him, “Yesterday felt like the fall of Saigon, with everybody rushing out of here as the whole world seemed to be coming apart, but today -- do you know what today feels like?”

.

He said, “No.”

.

.

He silently nodded and gave me a hug, and then he said good-bye.

.

After spending most of the following day organizing my belongings and making preparations to return to New Castle I took a break to get one last cup of coffee and to say good-bye to the baristas. The coffee shop was operating on a skeleton crew; it had all of the chairs stacked up on tables and there were never more than three customers in the store at a single time. There was, appropriately enough, carry-out service only.

.

I fell into a conversation with one of the newer baristas. I asked her, “How has the coronavirus affected you?” She said, “It’s depressing. It’s a strain because it means that I can’t get in as many hours of work as I would like to have, so I’m not sure how I will pay the bills.” She paused thoughtfully and added, “But it is changing the way we greet each other, isn’t it? I mean we used to say, ‘how are you doing?’ without really wanting to know how the other person is doing, but now people ask that question and actually mean it.”

.

She opened a bag of coffee beans for a customer and poured it into the grinding machine, “It forced me to think about what is most important in life,” she added, “Should my life be about endless work or should I spend more time on my relationships and appreciating the people around me?”

.

She turned on the machine and the blades started grinding the coffee beans, “At first I was thinking that I wasn’t concerned about the virus because I’m young and healthy, it doesn’t seem to be fatal for people like me. Then I started thinking about all the people I love, and many of them have compromised immune systems. I started thinking that it isn’t really about me, it’s about them, and now I want to fight anyone or anything to protect them from the virus.”

.

She resealed the bag of freshly ground coffee beans and handed them to the customer and began wiping the counter, “You know, in a strange way I think this is an opportunity to slow down and put things in perspective. I notice more people are taking walks, which might bring them closer to nature. I hope something good will come out of it and we will no longer go through life without really paying attention.”

.

I thanked her for her wisdom and left the store.

.

Back at the seminary, later that night, I lit some candles and spent a holy hour in what we have come to call the “JPII pew,” because Saint John Paul II prayed in that spot, in 1995. I gazed at the tabernacle and in stillness and silence I reflected on all my years in seminary formation, and on what will come next, God-willing, in the priesthood. I finally found the peace I was looking for. I finally reached some degree of closure. Now, I am ready to return to Pittsburgh and begin a new chapter in my life.