|

| Image Credit: Inspiriatus.org |

.

Freedom from a Commitment to Other People is Not Freedom at All

.

Brooks notes that freedom (if one means by it individual and social "freedom" in which one is not tied down to other people but is, rather, an individual who is adrift in the world), is not something you want to aim for. Such freedom, he says, is "not an ocean you want to live in; it is the river you want to get through so that you can commit yourself to something on the other side."

.

The uncommitted person, he says, is the unremembered person because a person who cannot make a commitment is not permanently attached to anyone or anything.

.

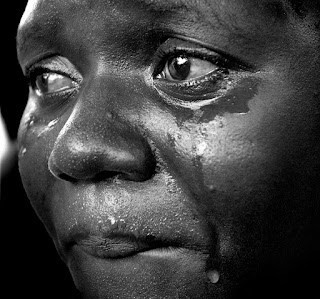

Breaking Open in the Season of Sorrow

.

Brooks goes on to discuss what he calls "the season of sorrow", which is the low point in each of our lives, and in the life of a society, where everything seems to be coming apart and it seems as though we cannot go on.

.

Brooks says that when you hit a hard patch in your life you can either be broken or you can be broken open. I take this phrase, "broken open" in the Eucharistic sense, in which one is made whole by allowing oneself to be vulnerable and to confront the pain and suffering.

.

Brooks says that people who are simply broken (not broken open) get smaller and more afraid; they lash out in anger and grievance toward the world and they are filled with resentment. They experience pain, and pain, Brooks notes, that is not transformed is soon transmitted onto others.

.

On the other hand, a person may be (Eucharistically) broken open. The toughest moments of our lives begin to define us when we are broken open; they are moments when we stop living superficially and we begin to discover the depths of our souls.

.

Wisdom from Suffering

|

| Image Credit: blog.bible |

Quoting Paul Tillich, Brooks says that suffering interrupts our lives and reminds us that we are not who we once thought we were.

.

Suffering, Brooks says, carves through what we thought was the basement of our soul and reveals a cavity below that "basement", and it carves through the floor of the cavity and reveals a cavity below that. It is through suffering, he says, that we come to know ourselves more deeply.

.

Brooks quotes Tillich in noting that in our suffering we discover our hearts and our deepest desire. We all have a sense of desire, Brooks says. Sometimes life tries to cover over that desire, but our desire shoots through. What the heart desires most is the sense of completion and fusion with another. One might add that in the tradition of the Abrahamic religions, our deepest desire is to become one community and to see the face of God.

.

Love and the Yearning of the Soul

.

Love, Brooks points out, is more than infatuation. It is more than a passing feeling and a mere emotion. Quoting British novelist Louis de Bernières, Brooks notes that love is what is left over when "being in love" is burned away. Love endures the temporal, the fleeting, and the transitory.

.

It is during what Brooks calls "the season of our suffering" that we discover that we have a yearning soul.

.

Brooks does not attempt to play the role of a theologian, but he offers his audience this working definition of a soul: it is a piece of us that has no size, weight, color or shape. He says of the soul that it is of infinite value and dignity and that rich and successful people do not have more of it than do poorer or less financially successful people.

.

The abuse of human persons, he continues, is wrong not just because of the damage it does to the physical body, but because of the damage it does to the human soul. Harm to the body is worsened, in its effect, because of the harm it does at the deeper level of the soul.

.

The soul, Brooks says, gives us moral responsibility, and it also gives us the desire to lead good lives. He adds that as the heart yearns for fusion with another, the soul yearns for fusion with an ideal. It is this yearning for the transcendent and the ineffable that attracts us and pulls us upward.

.

In the dark moments of our lives, Brooks says, we become aware of our desire for values that are higher than the shallow desires that once defined us.

.

A Problem with Two Faces: Tribalism and Radical Individualism

.

|

| Image Credit: Facades-online.com |

.

Brooks sees the United States today as being in a moment that he would characterize as being a season of suffering. This moment, he says, has been in the making for more than 40 years.

.

The United States is damaged, he says, by the loss of a sense of connection between people, by our hyper-individualism, and by a distorted and obsessive concern for meritocracy to the point that we place greater value on some people's lives over others based on how much wealth they have and how much money they make. We define our worth as human beings by how much social status we have and how much we can consume.

.

The problems our society faces, according to Brooks, are personal as well as social. Our individual stories map onto the larger story of our society as a whole. Our hyper-individualism weakens the connection between us; we also find it harder and harder to trust one another and we find it harder to trust our institutions (religious, media, academic, and political). We also suffer, he says, from a crisis of the spirit so that many people no longer believe that there is anything for which to live.

.

Brooks points out that the growth of "tribalism" in our society today is a symptom of the problem. He sees tribalism as being a negative form of social identity and social relationship. People seek comfort in the feeling of tribalism when they are afraid of everyone and everything that is outside of the tribe. Tribalism thrives in an environment of fear and hate.

.

Fear and Recovery

|

| Image credit: quuf.org |

Fear, Brooks argues, is a driving force in our society today, and it generates a form of energy that is tearing us apart. Recovery, according to Brooks, will require a four-step process:

.

First, our culture will have to be willing to be broken open. Although Brooks does not put it quite in this way I would look at it from a Christian standpoint and see the model for being broken open reflected in the celebration of the Eucharist.

.

Brooks, who is Jewish, gives an example of this from rabbinic teaching based on a parable in the Hebrew Scriptures related to Moses in which a lamb flees deep into the wilderness. The rabbinic teaching points out that sometimes, like that lamb, we must flee deep into the territory of the unfamiliar so that we can see the world around us in a different light.

.

Brooks argues that when we get down to the bottom of who we are, as human beings, regardless of differences in culture, politics, and ideology, we will find an inexplicable capacity to care for one another. We are often surprised to find this inexplicable capacity to care even among those whom we think of as being our "enemies".

.

Quoting Anne Dillard, Brooks points out that once you get below our identity politics, our social posturing and the various masks we wear to define ourselves, most of us simply want to know that we are loved. This, of course, is what is at the core of the Gospels and the Hebrew Scriptures as well as other sacred writing in the Abrahamic tradition; it is the journey of a people who know that they are beloved by God and are able to pay that love forward.

.

Salvation in Community

.

Secondly, says Brooks, you have to be willing to be led. He notes that we are not able to get ourselves out of seasons of suffering on our own power. This reminds me of something Pope Benedict XVI used to say: "You cannot pull yourself out of the quicksand by your own hair."

.

We need other people to lift us out of our season of suffering. In the Abrahamic tradition, and especially from the standpoint of Christian theology, God works through other people to lift us up from the mire from which we cannot free ourselves under our own power. This is why the notion of "kenosis" (the self-emptying of Jesus) is so important in Christian theology and is something all Christians are called to imitate in their own lives; it is a self-emptying that frees one to become an instrument to others of God's healing.

.

Brooks points out the importance of relationships and communities. Often, when we search for solutions to personal and societal problems we think in terms of what "program" might be helpful. Brooks quotes a person, Bill Milliken, who had been doing youth work for 50 years who said, "I have never seen a program turn around a life; I've only seen relationships turn lives around."

.

This requires the willingness to allow oneself to be led. Only when we open up can we allow ourselves to be led out of our spiritually-oppressive self-absorption and isolation.

.

The Bright Sadness

.

.

Brooks notes, of these people that "they see reality, they see the shadows because they are right in the middle of life, but they have a brightness about it." At the core of their perspective on life is a sense of "radical hospitality" and "radical mutuality" born of the understanding that we are "all equal" because we are "all broken". From this awareness, they extract the capacity to transcend themselves and live for others.

|

| Image credit: crosswalk.com |

Brooks concludes that by being loved we develop the capacity to give and express love and that we are not meant to live as hyper-individualists: "we are formed by relationships; we live by relationships; we measure our lives by the quality of our relationships, and society shifts when the culture shifts."

.

Brooks makes one other observation, which I believe is particularly important to keep in mind in terms of the life of our parishes: "communities are people who share a sense of story." How often we overlook this. This is why it is so important for parish pastoral councils to be involved in conducting in-depth interviews with a significant number of parishioners. This must be done not only to develop a pastoral plan but, in the process of developing the plan, to excavate the story of the parish which, in turn, will strengthen a sense of belonging to a community among parishioners. Every parish has a story. Every parish IS a story which maps onto the larger story of the universal Church.

.

Brooks notes that "if you don't have a story that you are a part of, you don't know how to behave." Paraphrasing Brooks, which I have done a lot of in this post tonight, some parishes are all-too-aware of their story, but the story they embrace is from decades ago. Their story has stagnated and become outdated, as has their parish identity. In those cases, it is necessary for the parish to refresh and renew their story by updating it, reflecting the lives of the people in the parish territory today while honoring the stories of previous generations. Who are we today? What are our lives like, and what is the social environment of our parish today, as opposed to what it was one or two generations ago?

.

"Happiness" and Joy

.

Significantly, Brooks distinguishes between "happiness" and "joy". Happiness, he says, "is when you win a victory and your 'self' expands", but "joy" is "what you feel when you transcend 'self'", and you lose the alienating distinction between where you end and somebody else begins. Joy, he says, becomes more than just a fleeting feeling, it develops into an outlook that you live from day-to-day.

.

Brooks closes with these memorable words: "If we orient ourselves toward joy, not just individual happiness, then we will be pointed in the right direction."