Saturday, November 25, 2017

In Silence: The Apostolate of the Ear

In silence, we are better able to listen to and understand ourselves; ideas come to birth and acquire depth; we understand with greater clarity what it is we want to say and what we expect from others, and we choose how to express ourselves. By remaining silent we allow the other person to speak, to express him or herself; and we avoid being tied simply to our own words and ideas without them being adequately tested.” (Pope Benedict XVI, May 20, 2012)

Tuesday, June 20, 2017

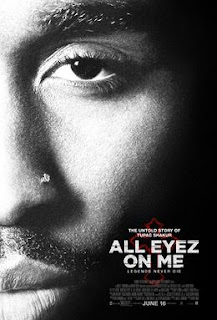

Tupac Shakur: Soul of African American Conflict and Survival

I just got back, a few hours ago, from watching “All Eyez on Me,” a movie about the life and death of Tupac Shakur. In many ways, the movie traces the struggles, conflicts, contradictions, and decline of the African American community from the early 1970s until the mid-1990s.

Shakur, in this movie, was a tragic hero whose background, which was a quintessentially American hybrid of Afrocentric nationalism and Shakespearean city theater, gave him a vision of what he should aspire to while also sowing the seeds of his destruction.

The struggle against oppression and the attempt to adhere to principle comes at a heavy cost, as both Tupac and his mother learned over the arc of their lives. Tupac’s rise to stardom occurred within the tension of one who sees himself as being someone who has the power to spark the rise of a liberating form of self-awareness and to raise the consciousness of African American communities, and, on the other hand, one who sees himself as being merely an entertainer whose primary goal is to sell more records.

In the 1992 movie “Juice”, Tupac played the role of "Bishop," who was a chilling sociopath. The image worked for him and he may have internalized the persona. Still, this image was at odds with the values that his mother tried to instill in him since childhood.

Tupac's struggle with becoming something that he wasn't, while claiming he was expressing what was inside of him all along, became a recurring theme. On some level, the sociopath character, Bishop, channeled Tupac's childhood anger and gave it a creative outlet. The internal struggle that was emerging is foreshadowed in "All Eyez on Me" when Tupac's stepfather says to him, “Sometimes people need to step out of who they are to realize what they can be.”

In the film, Shakur tried to rationalize his misogynist outlaw popular image, which boosted him to stardom, with his grounding in the mixture of the Gospel and Islamic sensibilities of African American culture and spirituality: a spirituality of suffering, redemption, and resilience. It is a spirituality of survival.

Again, and again, however, he found himself making deals with the devil in order to rise to the top of his game, and in order to survive, when the authorities and his contemporaries were trying to destroy him.

The influence he had on several generations of young black males came at the cost of the corruption of his ideals. He reconciled the conflict between his image and his ideas by saying, “You’ve got to enter into somebody’s world in order to lead them out of it.”

When he was finally sitting on top of the kingdom of rap, at such great cost to his core values, it wouldn’t be a surprise to discover that he was thinking, like Shakespeare’s Henry IV, “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown.”

Tupac is depicted in the film as a man with a message, although, at 25, with all of the seductions of self-indulgence at his fingertips, the messenger often lost his way.

Nonetheless, the importance of the message remained. During one scene in the movie a record company executive told him that his lyrics were too raw and that people just wanted to be entertained, Tupac replied, “Some people just want to be entertained; other people want a chance to speak. I’m reporting from the streets. I’m educating and keeping it real.”

The sample of hip hop from the early 1990s, especially from Tupac’s long-forgotten Digital Underground days, had me dancing in my seat. Funny how all of that comes back to you with irresistible force when you haven’t heard the music for 25 years.

The film, like Tupac’s life, touched base with locations that were significant for very different reasons and in very different ways, for African American culture in the ‘70s through the ‘90s: Harlem, Baltimore, The San Francisco Bay Area, Brooklyn, and Compton.

All Eyez on me captures the best and worst of the struggle for survival in African American communities. It also captured the hyper-materialist popular culture of the 1990s. Tupac grew up believing, with good reason, that the biggest threat to his survival came from forces beyond African American communities; by the end of the film, he realized that the community is often complicit in its own destruction.

This is not to say that the external threats weren't real. When Tupac’s mother realized that powerful people saw what an influence he had over young people, and perceived him as a threat, she pleaded with him to be careful: “They are going come after you with everything that you love. They are going to give you the tools that you need to destroy yourself.”

The movie presents an all-too-human story of the contradiction between the best and the worst that is inside of us.

Shakur, in this movie, was a tragic hero whose background, which was a quintessentially American hybrid of Afrocentric nationalism and Shakespearean city theater, gave him a vision of what he should aspire to while also sowing the seeds of his destruction.

The struggle against oppression and the attempt to adhere to principle comes at a heavy cost, as both Tupac and his mother learned over the arc of their lives. Tupac’s rise to stardom occurred within the tension of one who sees himself as being someone who has the power to spark the rise of a liberating form of self-awareness and to raise the consciousness of African American communities, and, on the other hand, one who sees himself as being merely an entertainer whose primary goal is to sell more records.

In the 1992 movie “Juice”, Tupac played the role of "Bishop," who was a chilling sociopath. The image worked for him and he may have internalized the persona. Still, this image was at odds with the values that his mother tried to instill in him since childhood.

Tupac's struggle with becoming something that he wasn't, while claiming he was expressing what was inside of him all along, became a recurring theme. On some level, the sociopath character, Bishop, channeled Tupac's childhood anger and gave it a creative outlet. The internal struggle that was emerging is foreshadowed in "All Eyez on Me" when Tupac's stepfather says to him, “Sometimes people need to step out of who they are to realize what they can be.”

In the film, Shakur tried to rationalize his misogynist outlaw popular image, which boosted him to stardom, with his grounding in the mixture of the Gospel and Islamic sensibilities of African American culture and spirituality: a spirituality of suffering, redemption, and resilience. It is a spirituality of survival.

Again, and again, however, he found himself making deals with the devil in order to rise to the top of his game, and in order to survive, when the authorities and his contemporaries were trying to destroy him.

The influence he had on several generations of young black males came at the cost of the corruption of his ideals. He reconciled the conflict between his image and his ideas by saying, “You’ve got to enter into somebody’s world in order to lead them out of it.”

When he was finally sitting on top of the kingdom of rap, at such great cost to his core values, it wouldn’t be a surprise to discover that he was thinking, like Shakespeare’s Henry IV, “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown.”

Tupac is depicted in the film as a man with a message, although, at 25, with all of the seductions of self-indulgence at his fingertips, the messenger often lost his way.

Nonetheless, the importance of the message remained. During one scene in the movie a record company executive told him that his lyrics were too raw and that people just wanted to be entertained, Tupac replied, “Some people just want to be entertained; other people want a chance to speak. I’m reporting from the streets. I’m educating and keeping it real.”

The sample of hip hop from the early 1990s, especially from Tupac’s long-forgotten Digital Underground days, had me dancing in my seat. Funny how all of that comes back to you with irresistible force when you haven’t heard the music for 25 years.

The film, like Tupac’s life, touched base with locations that were significant for very different reasons and in very different ways, for African American culture in the ‘70s through the ‘90s: Harlem, Baltimore, The San Francisco Bay Area, Brooklyn, and Compton.

All Eyez on me captures the best and worst of the struggle for survival in African American communities. It also captured the hyper-materialist popular culture of the 1990s. Tupac grew up believing, with good reason, that the biggest threat to his survival came from forces beyond African American communities; by the end of the film, he realized that the community is often complicit in its own destruction.

This is not to say that the external threats weren't real. When Tupac’s mother realized that powerful people saw what an influence he had over young people, and perceived him as a threat, she pleaded with him to be careful: “They are going come after you with everything that you love. They are going to give you the tools that you need to destroy yourself.”

The movie presents an all-too-human story of the contradiction between the best and the worst that is inside of us.

Sunday, March 26, 2017

Out of the Cave (a poem)

Out of the Cave

By C. Matthew Hawkins

Spring, 2017

Baltimore

After what seemed like more than a lifetime

in dimly-lit rooms where the musty smell of unwashed clothes

and stale cigarette smoke still lingered in the air

something drew you to the door.

You stumbled through narrow hallways cluttered with empty soda bottles,

greasy boxes of half-eaten pizza, and large plastic bags filled with trash,

waiting to be emptied.

You bumped against smudged walls as you made your way to the door.

You reached for the knob and turned up your nose when you smelled the rotten wood.

The door gave a painful whine when you opened it.

As reckless as kids on dirt bikes in city streets dodging in and out of traffic,

cutting across alleys strewn with broken glass and across vacant lots overgrown with weeds.

They scraped their knees and blood rose to the surface of wounds too fresh to form scabs.

If you had hung on for the ride no telling where you would have ended up.

You could not trust the feelings that drew you out of the cave.

You tried to retreat into the safety of darkness but stubborn fascination insisted on more than just a glimpse.

You heard the roar of an approaching dirt bike, almost inviting you to hop aboard,

but you wouldn’t even think of riding along because you could not afford to lose control.

You could not see the face of the rider, whose ragged, blood-stained bandanna covered everything below the eyes.

How could you trust that which was partially concealed?

Yet above the tattered bloody cloth that flapped in the breeze as he zipped past,

the rider’s piercing eyes looked you dead in the face, and in an instant, he was gone.

Burning, soul-piercing, youthful eyes older than all the centuries

peered beneath a scar across his sweat-soaked brown forehead

and he disappeared as suddenly as he came.

It didn’t matter where the feeling came from that drew you into the sunlight,

your impulse was to turn away.

The feeling that drew you out refused to explain itself or to give you answers to all of your questions.

It was a moment of encounter that refused to be confined by your logic.

Your tongue felt like sand against the roof of your mouth and it reminded you that you thirst.

Gradually it dawned on you:

Mystery is not your inability to know; it is your inability to exhaust your thirst for what had been revealed.

Even as you tried to turn away revelation tightened its grip, cutting through layer upon layer of encrusted belief that you had woven over the years to hide you from yourself.

A Reading of the Poem during a practice session:

By C. Matthew Hawkins

Spring, 2017

Baltimore

|

| Image Credit: WBaltTV |

After what seemed like more than a lifetime

in dimly-lit rooms where the musty smell of unwashed clothes

and stale cigarette smoke still lingered in the air

something drew you to the door.

You stumbled through narrow hallways cluttered with empty soda bottles,

greasy boxes of half-eaten pizza, and large plastic bags filled with trash,

waiting to be emptied.

You bumped against smudged walls as you made your way to the door.

You reached for the knob and turned up your nose when you smelled the rotten wood.

The door gave a painful whine when you opened it.

***

Although the air outside was fresh you tensed,

flexing the muscles in your arms,

and tightening your fists into knots,

and scowling as you stared down the street,

nursing fear concealed as anger.

You thought anger would protect you,

but it suddenly dropped away like an unreliable bodyguard.

All that was left was your fear.

In that brief moment, you were exposed.

Light passed through the summer mist, which rose from the sidewalk after the rain.

The air was sweet.

All things were new again.

***

Sunlight cut across your eyes;

You squinted with a pout, trying to turn away

but you could swear you caught a glimpse of the very figures of love, truth and freedom

strolling through the haze.

You snapped your head back to where the figures were, but they are gone.

***

You shook your head to clear it of thoughts and feelings that could not be trusted.

The feeling was strange and new, yet it had shadowed you for years.

Comfortably familiar, yet disturbingly unexpected, you searched for traces of the elusive figures

and you knew this search was reckless.

***

cutting across alleys strewn with broken glass and across vacant lots overgrown with weeds.

They scraped their knees and blood rose to the surface of wounds too fresh to form scabs.

If you had hung on for the ride no telling where you would have ended up.

You could not trust the feelings that drew you out of the cave.

You tried to retreat into the safety of darkness but stubborn fascination insisted on more than just a glimpse.

You heard the roar of an approaching dirt bike, almost inviting you to hop aboard,

but you wouldn’t even think of riding along because you could not afford to lose control.

|

| Image Credit: 12 O' Clock Boys Film |

You could not see the face of the rider, whose ragged, blood-stained bandanna covered everything below the eyes.

How could you trust that which was partially concealed?

Yet above the tattered bloody cloth that flapped in the breeze as he zipped past,

the rider’s piercing eyes looked you dead in the face, and in an instant, he was gone.

Burning, soul-piercing, youthful eyes older than all the centuries

peered beneath a scar across his sweat-soaked brown forehead

and he disappeared as suddenly as he came.

|

| Image Credit: 12 O' Clock Boys Film |

It didn’t matter where the feeling came from that drew you into the sunlight,

your impulse was to turn away.

The feeling that drew you out refused to explain itself or to give you answers to all of your questions.

It was a moment of encounter that refused to be confined by your logic.

Your tongue felt like sand against the roof of your mouth and it reminded you that you thirst.

Gradually it dawned on you:

Mystery is not your inability to know; it is your inability to exhaust your thirst for what had been revealed.

Even as you tried to turn away revelation tightened its grip, cutting through layer upon layer of encrusted belief that you had woven over the years to hide you from yourself.

|

| Image Credit: Baltimore Police Department |

A Reading of the Poem during a practice session:

Sunday, February 19, 2017

"I Am Not Your Negro": A Witness to History and Violence

Novelist and essayist James Baldwin began a project, shortly before he died, to explore recent American history reflected through the lens of three pivotal figures: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King. These three figures represent three aspects of African American thought in the mid-20th century. Baldwin's voice adds a fourth dimension to the narrative.

Baldwin's narration in the movie, spoken by Samuel L. Jackson, weaves the themes of how America defines its heroes, the concept of racial "purity," the narrative of "innocence" despite a history of violence, and what it means to be a "witness." Baldwin wraps these themes around his encounters with Medgar, Malcolm and Martin and their widows.

The movie begins with Baldwin in exile, in France, contemplating what it means to "pay one's dues," during the struggle for racial equality in the United States. His reflections on being a bystander, and also on many of his countrymen's apathy and indifference toward that effort, lead him to return home. As a writer, he must be a witness to history and document it.

The central question in the film, as Baldwin articulates it, is not "What will become of the [Black American]?" but "What will become of America" if it continues on the path on which it is headed?

An underlying question throughout the film is, "What is the state of a civilization that produces such violence?"

Baldwin evaluates American history not so much by its words or its professed ideals, but by the behavior of its institutions, especially its religious institutions.

Noting that the present is both a departure from, and a continuation of the past Baldwin writes, at one point in the film: "We are our history."

At another point, he makes an observation that might serve as the overarching theme and the purpose of making the movie: "Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can change until it has been faced."

Baldwin's narration in the movie, spoken by Samuel L. Jackson, weaves the themes of how America defines its heroes, the concept of racial "purity," the narrative of "innocence" despite a history of violence, and what it means to be a "witness." Baldwin wraps these themes around his encounters with Medgar, Malcolm and Martin and their widows.

The movie begins with Baldwin in exile, in France, contemplating what it means to "pay one's dues," during the struggle for racial equality in the United States. His reflections on being a bystander, and also on many of his countrymen's apathy and indifference toward that effort, lead him to return home. As a writer, he must be a witness to history and document it.

The central question in the film, as Baldwin articulates it, is not "What will become of the [Black American]?" but "What will become of America" if it continues on the path on which it is headed?

An underlying question throughout the film is, "What is the state of a civilization that produces such violence?"

Baldwin evaluates American history not so much by its words or its professed ideals, but by the behavior of its institutions, especially its religious institutions.

Noting that the present is both a departure from, and a continuation of the past Baldwin writes, at one point in the film: "We are our history."

At another point, he makes an observation that might serve as the overarching theme and the purpose of making the movie: "Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can change until it has been faced."

Friday, January 20, 2017

When Character and Virtue are Tested...

Tonight I saw the movie Silence, which Martin Scorsese directed. The truth of the matter is that I wasn't looking forward to seeing the film because I thought it would be an overly-simplified, Western "good guys" versus Eastern "bad guys" movie. It wasn't like that at all.

This was a complex film about two Jesuit priests who ventured in 17th century Japan under conditions of religious repression. They were searching for a priest who arrived in the country earlier and was said to have become an apostate.

The movie was also as much about the enduring faith of the peasantry, after more than a generation of brutal treatment to destroy their communities, as it was about the fate of the three priests who were focal points in the story.

The acting was engaging, and the scenery was enthralling. The script and the story were intellectually stimulating. The movie depicted the often subtle methods of psychological torture along with the more direct forms of physical abuse.

Friends who have read the novel that the movie is based on said that the film is an accurate depiction of the printed text. The book itself is based on real events. A key theme in the film centers on the question of where God is in the midst of suffering. A brief passage offers an answer: one encounters God in the midst of the silence.

Although it was a thought-provoking film, it is not for an audience that has a short attention-span or for people who are uncomfortable and impatient with exploring the complexities of character and judgment.

The script presented compelling arguments about whether or not truth is universal or merely culturally-specific; the efficacy of symbolism and names, and the real meaning of "mercy."

If you watch this movie with a friend, or two, or six -- make sure you allow time for a good discussion afterward. You will most likely find yourself talking about the film for hours.

This was a complex film about two Jesuit priests who ventured in 17th century Japan under conditions of religious repression. They were searching for a priest who arrived in the country earlier and was said to have become an apostate.

The movie was also as much about the enduring faith of the peasantry, after more than a generation of brutal treatment to destroy their communities, as it was about the fate of the three priests who were focal points in the story.

The acting was engaging, and the scenery was enthralling. The script and the story were intellectually stimulating. The movie depicted the often subtle methods of psychological torture along with the more direct forms of physical abuse.

Friends who have read the novel that the movie is based on said that the film is an accurate depiction of the printed text. The book itself is based on real events. A key theme in the film centers on the question of where God is in the midst of suffering. A brief passage offers an answer: one encounters God in the midst of the silence.

Although it was a thought-provoking film, it is not for an audience that has a short attention-span or for people who are uncomfortable and impatient with exploring the complexities of character and judgment.

The script presented compelling arguments about whether or not truth is universal or merely culturally-specific; the efficacy of symbolism and names, and the real meaning of "mercy."

If you watch this movie with a friend, or two, or six -- make sure you allow time for a good discussion afterward. You will most likely find yourself talking about the film for hours.

Saturday, January 14, 2017

Fences, Collateral Beauty, Moonlight, and Hidden Figures: Movie Reviews

August Wilson's Fences explores a family caught between changing times and the ghosts of the past, and it conjures up the sights and sounds of the City of Pittsburgh during the 1950s.

The film is based on Wilson's play. It is heavily driven by dialogue and the complexity of the lives of the movie's main characters. For those who are tired of movies that overwhelm the senses with noise and visual special effects, Fences will be a refreshing change.

The movie is like walking into the scenes of a play and becoming part of the story. The script will appeal to those who are not interested in mostly going to movies for an escape. The family's story will reach into your heart, but you will get the most out of the film if you pay close attention to Wilson's use of two key metaphors: baseball and fences.

These two metaphors intensify an already emotionally powerful movie.

Fences is a gut-wrenching portrayal of growing old, coming of age, and coping with the hopes and disappointments of everyday life. Through moments of joy and sorrow, there is a touch of a miracle.

Collateral Beauty is likely to appeal to those who have a spiritual or a metaphysical bent. The movie draws out the way that literature addresses the topics of love, death and time. There were moments during the film when I thought that the screenwriter and the actors were trying too hard to be profound.

From the standpoint of storytelling, I thought that the movie sacrificed a well-crafted storyline to emphasize its message. The narrative aspect of the story was predictable and weak. There were parts in the third act that were downright hokey.

Also, the central character, which was played by Will Smith, was one-dimensional. It was hard to become emotionally invested in a character whose two emotions were angst and angst. And it was hard to understand why Jacob Latimore was selected for this film unless it was for his looks or to draw upon his fan base. It certainly wasn't because of his acting skills.

Nonetheless, it was a movie that left, for me, a ponderous aftertaste, especially once I had a chance to sleep on it.

There are two "ah-ha" moments in the movie; one which is explicit during the climax of the film and the other which is implied at the very end.

These ah-ha moments, especially the one hinted at the end, along with the use of literature to explore how we think about love, death and time, ultimately made the movie worth seeing.

Moonlight is a sensitive portrayal, which is artistically filmed, of a young man who is bullied by his peers and who lacks family support at home. In the pattern of the parable of "The Good Samaritan," he gains care and compassion from a most unlikely character in the story.

The filming was stunning, regarding color, setting, and imagery. The director's use of nonverbal communication through facial expressions, in particular with the lead character as a boy, was powerful, reminding me of the facial expressions in Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew'.

The narrative was choppy, although I believe the director and screenwriter were going for an "artsy" effect. Rather than holding together as a story, which would have allowed for character development and complications that would lead to a climax and resolution, the writer and director relied on a fragmented selection of scenes. These fragments will move the viewer to tears, but they are ultimately devoid of an underlying story or satisfactory transitions between each leap in the three stages of the protagonist's development.

The movie includes sensitive subject-matter concerning violence, sexuality, and substance abuse. It is not light viewing, but worth seeing for thoughtful audiences.

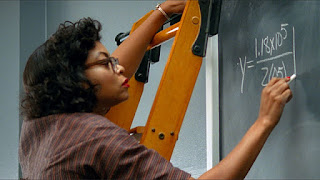

Hidden Figures is based on the true story of three women who worked for NASA in the 1960s through the early 1970s, overcoming social conventions and assumptions to make vital contributions to America's space program.

Not only were these women "hidden figures" because it did not fit the dominant narrative to acknowledge their contributions, but they also had to create resources and opportunities for themselves that others took for granted as being "just the way things are."

The title is a play on words reflecting both the method of cracking the puzzle of manned space flight (look for the "hidden figure" which conventional math cannot detect) and the practice of hiding these women's contributions from history.

The acting was excellent, and the story held the audience in suspense, which was quite a feat given the fact that we already knew the outcome of the main event that served as a backdrop for the story.

I recommend that parents bring their sons and daughters, teachers bring their students and moviegoers of all ages just kick back and enjoy the film. Your time will be well spent.

It was a gripping story with a subtle but timeless message: no nation or institution can afford to continue to waste and undermine its own talent, and real leadership requires the capacity to think anew rather than to suppress genius.

The film is based on Wilson's play. It is heavily driven by dialogue and the complexity of the lives of the movie's main characters. For those who are tired of movies that overwhelm the senses with noise and visual special effects, Fences will be a refreshing change.

The movie is like walking into the scenes of a play and becoming part of the story. The script will appeal to those who are not interested in mostly going to movies for an escape. The family's story will reach into your heart, but you will get the most out of the film if you pay close attention to Wilson's use of two key metaphors: baseball and fences.

These two metaphors intensify an already emotionally powerful movie.

Fences is a gut-wrenching portrayal of growing old, coming of age, and coping with the hopes and disappointments of everyday life. Through moments of joy and sorrow, there is a touch of a miracle.

Collateral Beauty is likely to appeal to those who have a spiritual or a metaphysical bent. The movie draws out the way that literature addresses the topics of love, death and time. There were moments during the film when I thought that the screenwriter and the actors were trying too hard to be profound.

From the standpoint of storytelling, I thought that the movie sacrificed a well-crafted storyline to emphasize its message. The narrative aspect of the story was predictable and weak. There were parts in the third act that were downright hokey.

Also, the central character, which was played by Will Smith, was one-dimensional. It was hard to become emotionally invested in a character whose two emotions were angst and angst. And it was hard to understand why Jacob Latimore was selected for this film unless it was for his looks or to draw upon his fan base. It certainly wasn't because of his acting skills.

Nonetheless, it was a movie that left, for me, a ponderous aftertaste, especially once I had a chance to sleep on it.

There are two "ah-ha" moments in the movie; one which is explicit during the climax of the film and the other which is implied at the very end.

These ah-ha moments, especially the one hinted at the end, along with the use of literature to explore how we think about love, death and time, ultimately made the movie worth seeing.

Moonlight is a sensitive portrayal, which is artistically filmed, of a young man who is bullied by his peers and who lacks family support at home. In the pattern of the parable of "The Good Samaritan," he gains care and compassion from a most unlikely character in the story.

The filming was stunning, regarding color, setting, and imagery. The director's use of nonverbal communication through facial expressions, in particular with the lead character as a boy, was powerful, reminding me of the facial expressions in Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew'.

The narrative was choppy, although I believe the director and screenwriter were going for an "artsy" effect. Rather than holding together as a story, which would have allowed for character development and complications that would lead to a climax and resolution, the writer and director relied on a fragmented selection of scenes. These fragments will move the viewer to tears, but they are ultimately devoid of an underlying story or satisfactory transitions between each leap in the three stages of the protagonist's development.

The movie includes sensitive subject-matter concerning violence, sexuality, and substance abuse. It is not light viewing, but worth seeing for thoughtful audiences.

Hidden Figures is based on the true story of three women who worked for NASA in the 1960s through the early 1970s, overcoming social conventions and assumptions to make vital contributions to America's space program.

Not only were these women "hidden figures" because it did not fit the dominant narrative to acknowledge their contributions, but they also had to create resources and opportunities for themselves that others took for granted as being "just the way things are."

The title is a play on words reflecting both the method of cracking the puzzle of manned space flight (look for the "hidden figure" which conventional math cannot detect) and the practice of hiding these women's contributions from history.

The acting was excellent, and the story held the audience in suspense, which was quite a feat given the fact that we already knew the outcome of the main event that served as a backdrop for the story.

I recommend that parents bring their sons and daughters, teachers bring their students and moviegoers of all ages just kick back and enjoy the film. Your time will be well spent.

It was a gripping story with a subtle but timeless message: no nation or institution can afford to continue to waste and undermine its own talent, and real leadership requires the capacity to think anew rather than to suppress genius.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)